Readings for Multimodal History

In my Digital Public History course, we are covering the topic of multimodality over the next week. I’ve put together some introductory readings for the class and thought that others might find them useful or interesting, To be clear, these readings are not comprehensive and give only a taste of the scholarship on the topic.

What is Multimodality?

At its core, the concept of multimodality is relatively simple. Defined by Eve Bearne and Helen Wolstencroft, "Multimodality involves the complex interweaving of word, image, gesture and movement, and sound, including speech. These can be combined in different ways and presented through a range of media." (Bearne, Eve, and Helen Wolstencroft. Visual Approaches to Teaching Writing: Multimodal Literacy 5 - 11. SAGE, 2007). The concept of multimodality recognizes that communication is rarely limited to a single communicative mode. For example, when we talk to to each other, we express ideas with our eyes, our demeanor, our volume, and our movements in addition to the words we use.

A substantial literature on multimodality has developed over the past few decades. This module will not be a comprehensive introduction to the theory and application of multimodality. Rather, it will introduce some core concepts that have immediate relevance for digital public history.

Let's start by defining two terms that are sometimes confusing when talking about multimodality: "mode/modality" and "medium."

Mode/Modality

Mode (or modality) refers to the way in which actors bundle together representational signals to convey meaning. These meanings might be as simple as a warning (for example, the various cues to stop conveyed by a stop sign), or they might be complex (for example, the non-linear narrative embodied in René Magritte's "The Treachery of Images." (https://youtu.be/atHQpANmHCE). These bundles of representational signals--what semioticians refer to as "signs"--are culturally and contextually specific. The signs we use to convey meaning depend on culturally specific and constantly shifting cultural lexicons. Lexicons help us understand each other, but we have all experienced moments when we don't understand the cultural lexicon or misinterpret signs and have misread the social situation.

Mode refers to the various ways in which signs (and clusters of signs) can be exchanged. Signs might make use of color, sound, shape, space, or movement to convey an idea or set of ideas.

Most of the time, meaning is made through a combination of modalities--or, what we might call multimodality. Take, for example, the most basic page in the most basic book. In addition to the text, there are other modes to convey meaning on every page: paragraph breaks, margins, font, color, and even paper stock (this sometimes conveys not only the monetary value of the book, but the value that the publishing community places in the ideas within the book). Users experience these modes with their eyes, through the feel of the book in their hands, and even the smell of the pages.

Let's have a look at a stop sign. As basic as it is, it's actually a multimodal object. The word "STOP" is linguistic, while the layers of colors and octagonal shape are visual. And, when reading the stop sign in its context, there is a spatial component as well in that it is situated in reference to other signs and spaces--for example crosswalks, other signs, lines painted on the road, buildings, curbs, and street signs--all of which give more contextual meaning to the stop sign.

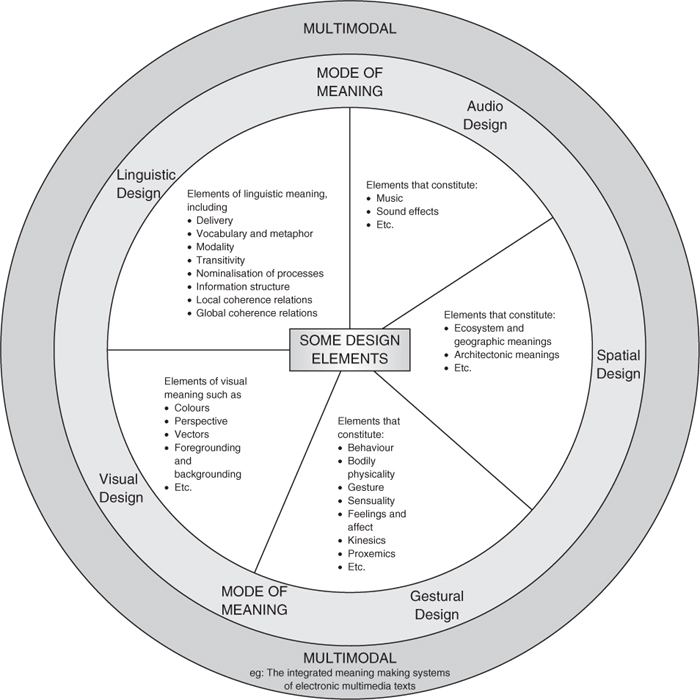

Scholars generally refer to five primary modes:

Linguistic

Aural / Audio

Visual

Gestural

Spatial

When two or more of these modes are brought together in the process of communication, it is multimodal. This visualization (which is itself multimodal) helps show how modes work together.

Caroline Haythornthwaite and Richard Andrews. “New Literacies, New Discourses in E-Learning.” In E-Learning Theory and Practice, 63–80. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2011. https://www.doi.org/10.4135/9781446288566.n5.

Medium/Media

A medium (pl. media) is the technology used to communicate. Media include books (yes, books are technologies, and it's important to keep this in mind), radio signals, paintings, prints, websites, and more.

In the most basic sense, the medium is the carrier of a sign. The medium can help determine which modes are relevant, or even possible, for conveying the meaning.

Let's return to the example of the stop sign. As we've already seen, the modalities of the stop sign include linguistic, visual, and spatial features. The medium is the physical stop sign itself.

Sometimes--and this is especially relevant for the digital humanities--communications scholars distinguish between "old media" and "new media." To some extent, this division is entirely arbitrary. In the 1960s, television was a new medium, but in the 2020s, it is an old medium. In contemporary parlance "new media" is digital, and "old media" is analog. However, don't be surprised to see television referred to as "new media" when reading older work in communications.

Modalities and Media for Historians

Historians have traditionally focused on linguistic modalities, so the media they have typically worked with have been books, letters, and journals. As scholars have expanded the modes they study to include images, space, sound, and gestures, the media with which they engage has expanded to include video, audio recordings, and even computer code. And, while historians have traditionally shared their work in a linguistic modality, in recent years, they have expanded the media through which they communicate. Podcasts, tabletop games, and even VR are just a few of the old and new media that historians (and especially public historians) employ in their work. This is all to say that the basics of communications theory are relevant to both the study of history and the communication with audiences.

In this section, I want to introduce you to a few key readings in anthropology, cultural studies, and media studies to give you a sense of the importance in paying close attention to modalities and media in both historical research and communication.

Example: Gesture as a Modality

While gestures are a "mode" for communicating something, they are not stable entities. Gestures might mean one thing in one cultural context, but something else in another cultural context. Likewise, the same gesture might mean multiple things in the same cultural context, only to be differentiated in the moment. Clifford Geertz explores some of the complexities of gesture in his essay "Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture" in Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1972), 5-10

In anthropology, or anyway social anthropology, what the practitioners do is ethnography. And it is in understanding what ethnography is, or more exactly what doing ethnography is, that a start can be made toward grasping what anthropological analysis amounts to as a form of knowledge. This, it must immediately be said, is not a matter of methods. From one point of view, that of the textbook, doing ethnography is establishing rapport, selecting informants, transcribing texts, taking genealogies, mapping fields, keeping a diary, and so on. But it is not these things, techniques and received procedures, that define the enterprise. What defines it is the kind of intellectual effort it is: an elaborate venture in, to borrow a notion from Gilbert Ryle, "thick description."

Ryle's discussion of "thick description" appears in two recent essays of his (now reprinted in the second volume of his Collected Papers) addressed to the general question of what, as he puts it, "Le Penseur" is doing: "Thinking and Reflecting" and "The Thinking of Thoughts." Consider, he says, two boys rapidly contracting the eyelids of their right eyes. In one, this is an involuntary twitch; in the other, a conspiratorial signal to a friend. The two movements are, as movements, identical; from an l-am-a-camera, "phenomenalistic" observation of them alone, one could not tell which was twitch and which was wink, or indeed whether both or either was twitch or wink. Yet the difference, however unphotographable, between a twitch and a wink is vast; as anyone unfortunate enough to have had the first taken for the second knows. The winker is communicating, and indeed communicating in a quite precise and special way: (I) deliberately, (2) to someone in particular, (3) to impart a particular message, (4) according to a socially established code, and (5) without cognizance of the rest of the company. As Ryle points out, the winker has not done two things, contracted his eyelids and winked, while the twitcher has done only one, contracted his eye lids. Contracting your eyelids on purpose when there exists a public code in which so doing counts as a conspiratorial signal is winking. That's all there is to it: a speck of behavior, a fleck of culture, and voilà!-a gesture.

That, however, is just the beginning. Suppose, he continues, there is a third boy, who, "to give malicious amusement to his cronies," parodies the first boy's wink, as amateurish, clumsy, obvious, and so on. He, of course, does this in the same way the second boy winked and the first twitched: by contracting his right eyelids. Only this boy is neither wink ing nor twitching, he is parodying someone else's, as he takes it, laugh able, attempt at winking. Here, too, a socially established code exists (he will "wink" laboriously, overobviously, perhaps adding a grimace-the usual artifices of the clown); and so also does a message. Only now it is not conspiracy but ridicule that is in the air. If the others think he is actually winking, his whole project misfires as completely, though with somewhat different results, as if they think he is twitching. One can go further: uncertain of his mimicking abilities, the would-be satirist may practice at home before the mirror, in which case he is not twitching, winking, or parodying, but rehearsing; though so far as what a camera, a radical behaviorist, or a believer in protocol sentences would record he is just rapidly contracting his right eyelids like all the others. Complexities are possible, if not practically without end, at least logically so. The original winker might, for example, actually have been fake-wink ing, say, to mislead outsiders into imagining there was a conspiracy afoot when there in fact was not, in which case our descriptions of what the parodist is parodying and the rehearser rehearsing of course shift accordingly. But the point is that between what Ryle calls the "thin description" of what the rehearser (parodist, winker, twitcher . . .) is doing ("rapidly contracting his right eyelids") and the "thick description" of what he is doing ("practicing a burlesque of a friend faking a wink to deceive an innocent into thinking a conspiracy is in motion") lies the object of ethnography: a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structures in terms of which twitches, winks, fake-winks, parodies, rehearsals of parodies are produced, perceived, and interpreted, and without which they would not (not even the zero-form twitches, which, as a cultural category, are as much nonwinks as winks are nontwitches) in fact exist, no matter what anyone did or didn't do with his eyelids.

Like so many of the little stories Oxford philosophers like to make up for themselves, all this winking, fake-winking, burlesque-fake-winking, rehearsed-burlesque-fake-winking, may seem a bit artificial. In way of adding a more empirical note, let me give, deliberately unpreceded by any prior explanatory comment at all, a not untypical excerpt from my own field journal to demonstrate that, however evened off for didactic purposes, Ryle's example presents an image only too exact of the sort of piled-up structures of inference and implication through which an ethnographer is continually trying to pick his way:

The French [the informant said] had only just arrived. They set up twenty or so small forts between here, the town, and the Marmusha area up in the middle of the mountains, placing them on promontories so they could survey the countryside. But for all this they couldn't guarantee safety, especially at night, so although the mezrag, trade-pact, system was supposed to be legally abolished it in fact continued as before.

One night, when Cohen (who speaks fluent Berber), was up there, at Marmusha, two other Jews who were traders to a neighboring tribe came by to purchase some goods from him. Some Berbers, from yet another neighboring tribe, tried to break into Cohen's place, but he fired his rifle in the air. (Traditionally, Jews were not allowed to carry weapons; but at this period things were so unsettled many did so anyway.) This attracted the attention of the French and the marauders fled.

The next night, however, they came back, one of them disguised as a woman who knocked on the door with some sort of a story. Cohen was suspicious and didn't want to let "her" in, but the other Jews said, "oh, it's all right, it's only a woman." So they opened the door and the whole lot came pouring in. They killed the two visiting Jews, but Cohen managed to barricade himself in an adjoining room. He heard the robbers planning to burn him alive in the shop after they removed his goods, and so he opened the door and, laying about him wildly with a club, managed to escape through a window.

He went up to the fort, then, to have his wounds dressed, and complained to the local commandant, one Captain Dumari, saying he wanted his 'ar i.e., four or five times the value of the merchandise stolen from him. The robbers were from a tribe which had not yet submitted to French authority and were in open rebellion against it, and he wanted authorization to go with his mezrag-holder, the Marmusha tribal sheikh, to collect the indemnity that, under traditional rules, he had coming to him. Captain Dumari couldn't officially give him permission to do this, because of the French prohibition of the mezrag relationship, but he gave him verbal authorization, saying, "If you get killed, it's your problem."

So the sheikh, the Jew, and a small company of armed Marmushans went off ten or fifteen kilometers up into the rebellious area, where there were of course no French, and, sneaking up, captured the thief-tribe's shepherd and stole its herds. The other tribe soon came riding out on horses after them, armed with rifles and ready to attack. But when they saw who the "sheep thieves" were, they thought better of it and said, "all right, we'll talk." They couldn't really deny what had happened-that some of their men had robbed Cohen and killed the two visitors-and they weren't prepared to start the serious feud with the Marmusha a scuffle with the invading party would bring on. So the two groups talked, and talked, and talked, there on the plain amid the thousands of sheep. and decided finally on five-hundred sheep damages. The two armed Berber groups then lined up on their horses at opposite ends of the plain, with the sheep herded between them, and Cohen, in his black gown, pillbox hat, and flapping slippers, went out alone among the sheep, picking out, one by one and at his own good speed, the best ones for his payment.So Cohen got his sheep and drove them back to Marmusha. The French, up in their fort, heard them coming from some distance ("Ba, ba, ba" said Cohen, happily, recalling the image) and said, "What the hell is that?" And Cohen said, "That is my 'ar." The French couldn't believe he had actually done what he said he had done, and accused him of being a spy for the rebellious Berbers, put him in prison, and took his sheep. In the town, his family, not having heard from him in so long a time, thought he was dead. But after a while the French released him and he came back home, but without his sheep. He then went to the Colonel in the town, the Frenchman in charge of the whole region, to complain. But the Colonel said, "I can't do anything about the matter. It's not my problem."

Quoted raw, a note in a bottle, this passage conveys, as any similar one similarly presented would do, a fair sense of how much goes into ethnographic description of even the most elemental sort-how extraordinarily "thick" it is. In finished anthropological writings, including those collected here, this fact-that what we call our data are really our own constructions of other people's constructions of what they and their compatriots are up to-is obscured because most of what we need to comprehend a particular event, ritual, custom, idea, or whatever is insinuated as background information before the thing itself is directly examined. (Even to reveal that this little drama took place in the highlands of central Morocco in 1912--and was recounted there in 1968--is to determine much of our understanding of it.) There is nothing particularly wrong with this, and it is in any case inevitable. But it does lead to a view of anthropological research as rather more of an observational and rather less of an interpretive activity than it really is. Right down at the factual base, the hard rock, insofar as there is any, of the whole enterprise, we are already explicating: and worse, explicating explications. Winks upon winks upon winks.

Analysis, then, is sorting out the structures of signification--what Ryle called established codes, a somewhat misleading expression, for it makes the enterprise sound too much like that of the cipher clerk when it is much more like that of the literary critic--and determining their social ground and import. Here, in our text, such sorting would begin with distinguishing the three unlike frames of interpretation ingredient in the situation, Jewish, Berber, and French, and would then move on to show how (and why) at that time, in that place, their copresence produced a situation in which systematic misunderstanding reduced traditional form to social farce. What tripped Cohen up, and with him the whole, ancient pattern of social and economic relationships within which he functioned, was a confusion of tongues.

I shall come back to this too-compacted aphorism later, as well as to the details of the text itself. The point for now is only that ethnography is thick description. What the ethnographer is in fact faced with except when (as, of course, he must do) he is pursuing the more automatized routines of data collection-is a multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit, and which he must contrive somehow first to grasp and then to render. And this is true at the most down-to-earth, jungle field work levels of his activity: interviewing informants, observing rituals, eliciting kin terms, tracing property lines, censusing households . . . writing his journal. Doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of "construct a reading of") a manuscript-foreign, faded, full of ellipses, incoherencies, suspicious emendations, and tendentious commentaries, but written not in conventionalized graphs of sound but in transient examples of shaped behavior.

To drive the point home a bit, there is an episode of Seinfeld in which the difference between a twitch and a wink makes all the difference. I think Clifford Geertz would have approved.

Example: Communicative Exchange

When thinking about multimodality, it's important to recognize that meaning-making is never unidirectional. In other words, the creator of meaning (for example, a writer or artist) can never fully control how the people receiving their messages will interpret them, ignore them, or use them in unintended ways. In the Seinfeld example, George speaks clearly and directly, but Kramer misinterprets his body language.

Another classic essay that explains these complexities is Stuart Hall's "Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse" (September 1972): https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-artslaw/history/cccs/stencilled-occasional-papers/1to8and11to24and38to48/SOP07.pdf

Example: Medium, Message, and Algorithm

Despite historians' expanded use of media to communicate, an expansion in their critical and historical analysis of these media hasn't necessarily accompanied this work (with the notable exceptions of scholars in the history of science and technology and in digital humanities). With so little focus on media, it's worthwhile to take a moment to examine why thinking about media is important. To do this, let's travel back to the 1960s to read a bit from Marshall McLuhan's, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, (McGraw Hill, 1964).

In a culture like ours, long accustomed to splitting and dividing all things as a means of control, it is sometimes a bit of a shock to be reminded that, in operational and practical fact, the medium is the message. This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium - that is, of any extension of ourselves - result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology. Thus, with automation, for example, the new patterns of human association tend to eliminate jobs, it is true. That is the negative result. Positively, automation creates roles for people, which is to say depth of involvement in their work and human association that our preceding mechanical technology had destroyed. Many people would be disposed to say that it was not the machine, but what one did with the machine, that was its meaning or message. In terms of the ways in which the machine altered our relations to one another and to ourselves, it mattered not in the least whether it turned out cornflakes or Cadillacs. The restructuring of human work and association was shaped by the technique of fragmentation that is the essence of machine technology. The essence of automation technology is the opposite. It is integral and decentralist in depth, just as the machine was fragmentary, centralist, and superficial in its patterning of human relationships.

The instance of the electric light may prove illuminating in this connection. The electric light is pure information. It is a medium without a message, as it were, unless it is used to spell out some verbal ad or name. This fact, characteristic of all media, means that the "content" of any medium is always another medium. The content of writing is speech, just as the written word is the content of print, and print is the content of the telegraph. If it is asked, "What is the content of speech?" it is necessary to say, "It is an actual process of thought, which is in itself nonverbal." An abstract painting represents direct manifestation of creative thought processes as they might appear in computer designs. What we are considering here, however, are the psychic and social consequences of the designs or patterns as they amplify or accelerate existing processes. For the "message" of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs. The railway did not introduce movement or transportation or wheel or road into human society, but it accelerated and enlarged the scale of previous human functions, creating totally new kinds of cities and new kinds of work and leisure. This happened whether the railway functioned in a tropical or a northern environment, and is quite independent of the freight or content of the railway medium. The airplane, on the other hand, by accelerating the rate of transportation, tends to dissolve the railway form of city, politics, and association, quite independently of what the airplane is used for.

Let us return to the electric light. Whether the light is being used for brain surgery or night baseball is a matter of indifference.

It could be argued that these activities are in some way the "content" of the electric light, since they could not exist without the electric light. This fact merely underlines the point that "the medium is the message" because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action. The content or uses of such media are as diverse as they are ineffectual in shaping the form of human association. Indeed, it is only too typical that the "content" of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium. It is only today that industries have become aware of the various kinds of business in which they are engaged. When IBM discovered that it was not in the business of making office equipment or business machines, but that it was in the business of processing information, then it began to navigate with clear vision. The General Electric Company makes a considerable portion of its profits from electric light bulbs and lighting systems. It has not yet discovered that, quite as much as AT&T, it is in the business of moving information.The electric light escapes attention as a communication medium just because it has no "content." And this makes it an invaluable instance of how people fail to study media at all. For it is not till the electric light is used to spell out some brand name that it is noticed as a medium. Then it is not the light but the "content" (or what is really another medium) that is noticed. The message of the electric light is like the message of electric power in industry, totally radical, pervasive, and decentralized. For electric light and power are separate from their uses, yet they eliminate time and space factors in human association exactly as do radio, telegraph, telephone, and TV, creating involvement in depth. A fairly complete handbook for studying the extensions of man could be made up from selections from Shakespeare. Some might quibble about whether or not he was referring to TV in these familiar lines from Romeo and Juliet:

But soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It speaks, and yet says nothing.

McLuhan's argument is that technologies are not neutral--that they are not simply carriers of meaning, but makers of meaning. In so doing, they transform human societies. Let's build on these insights just a bit by jumping ahead 55 years after McLuhan's initial insights to read a selection from Safiya Umoja Noble's Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (NYU Press, 2018). Noble's book has a number of important insights and arguments, including a perspective that 1) emphasizes the role that the builders of media (programmers and corporations) play in shaping the ways technologies function and 2) expands the argument that technologies are never neutral--especially when we examine their role in reproducing racist and patriarchal power systems.

In our reading from Algorithms of Oppression (pp. 1-63), Noble focuses on the algorithms behind Google's searches in shaping understanding:

Safiya Umoja Noble. Algorithms of Oppression : How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press; 2018. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1497317&site=eds-live

[NOTE: this reading includes screen shots of racist and misogynistic text and images from the internet, including sexualized images and graphic search engine results]

While we will not read it this semester, I encourage you to also read Ruha Benjamin's book, Race after Technology: the New Jim Code (Polity Press, 2019). Benjamin looks at the algorithms built into the digital media we use, which are effectively a "black box" that we never get to see inside but which their creators present as neutral. Benjamin argues that these algorithms reproduce racial inequities and are, in effect, a "New Jim Code”:

the employment of new technologies that reflect and reproduce existing inequities but that are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era. Like other kinds of codes that we think of as neutral, 'normal' names have power by virtue of their perceived neutrality.

Multimodal History

So far, we've spent quite a bit of time reading outside the field of history. This is, in part, because digital public history is interdisciplinary and requires engagement with multiple fields. We're going to continue this approach of engaging with texts and theories from other fields, even as we try to define what we mean by multimodal history. To get started, we're going to turn to a discipline that has close connections to the discipline of history--anthropology.

Multimodal Anthropology

To get started, please read

Collins, S.G., Durington, M. and Gill, H. (2017), Multimodality: An Invitation. American Anthropologist, 119: 142-146. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12826

Takaragawa, S., Smith, T.L., Hennessy, K., Alvarez Astacio, P., Chio, J., Nye, C. and Shankar, S. (2019), Bad Habitus: Anthropology in the Age of the Multimodal. American Anthropologist, 121: 517-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13265

Towards a Definition of Multimodal History

Conceptualizing "multimodal history" will be our task for our class meeting this week. Be sure to be ready to refer to your readings as we imagine how a "multimodal history" might help us better understand and practice of Digital Public History.

A Little Something Extra

I wanted to include the following video in this module, but it was already getting too long. So, I'm putting it here for any of you who might like an example of how to integrate the analysis of music into your work.

Music and sound are never there to fill an aural void. Rather, they are themselves rhetorical devices that might evoke mood, emphasize an idea, or generate an argument. To give you some sense of the complex ways in which music functions in communication, watch Adam Neely's analysis of Lady Gaga's and Michael Bearden's mixed meter Star Spangled Banner at the inauguration of Joe Biden.