Digital Audio for Public Historians (3): Microphone Types

We’ve finally gotten to microphones. A quality microphone might be the most important factor in creating a good recording rather than a bad recording.

I have already talked about onboard microphones a bit in the first entry in this series on recording devices. That’s pretty much all I have to say about built-in mics. They’re fine for getting the job done—if content is more important than quality.

For many public history applications, we would much prefer to have great content and a quality recording. To do this, we need good microphones that are set up so that they record what we want them to record and ignore what we want them to ignore.

Omnidirectional vs. Unidirectional (a.k.a. Cardioid) Mics

Perhaps the most basic distinction in microphones is that between omnidirectional and unidirectional (often called cardioid) mics. Omnidirectional mics capture sound equally from all sides of the microphone. Unidirectional mics capture sound from a specific direction.

Neither is necessarily better than the other. They just perform different functions. If you wanted to record a meeting of a dozen people around a table and you only had one mic, you would use an omnidirectional microphone placed in the middle of the table. It would capture sound equally from all directions. If you were recording a podcast between two people, and you had a studio and two mics, you would probably choose directional mics, positioned to capture the voice of each individual speaker.

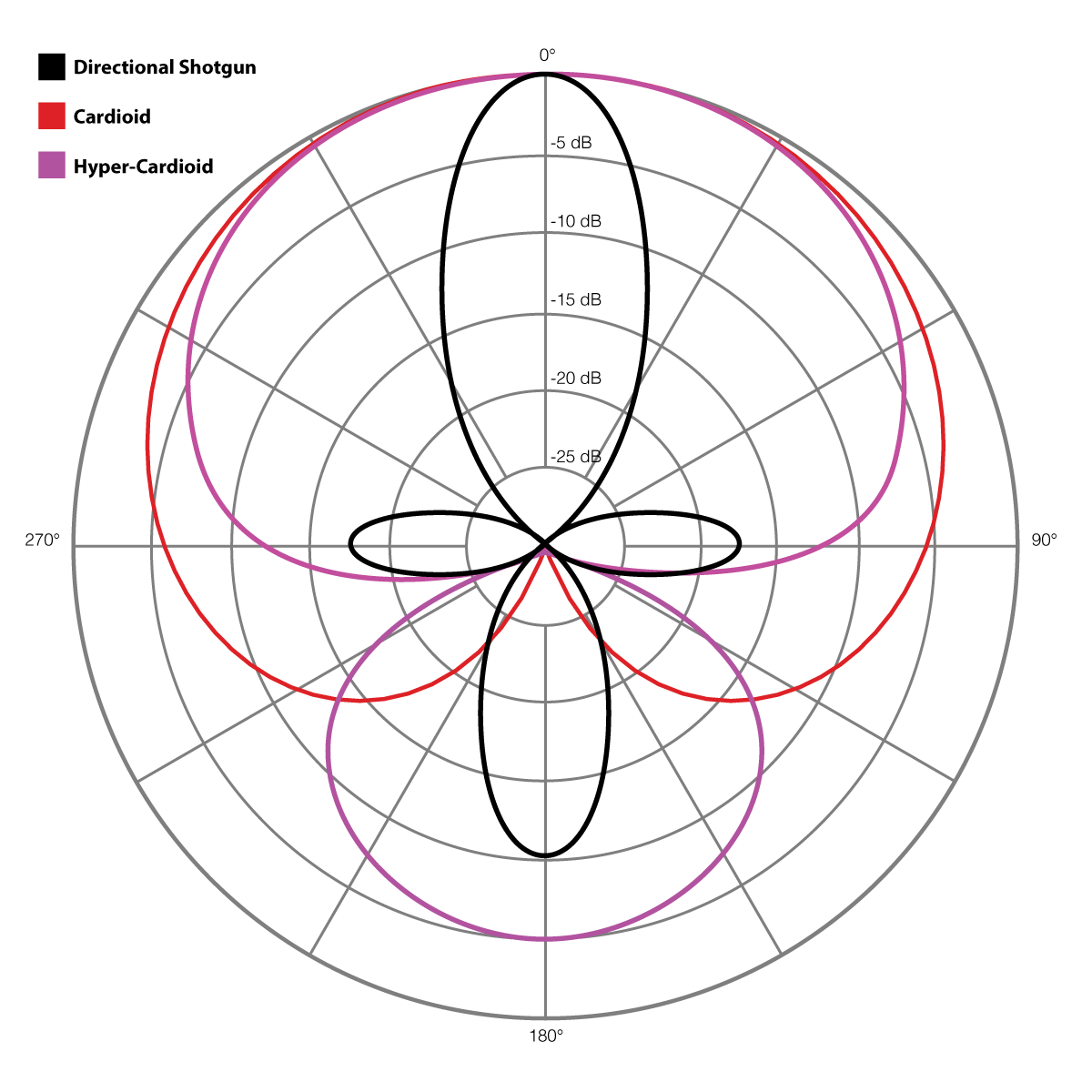

There are lots of variations on cardioid mics. For example, as its name implies a bidirectional mic (a.k.a. figure-8 mic) picks up sound from the front and back of the mic while reducing sound from the sides. A shotgun mic, focuses on picking up sound into the distance directly in front of it.

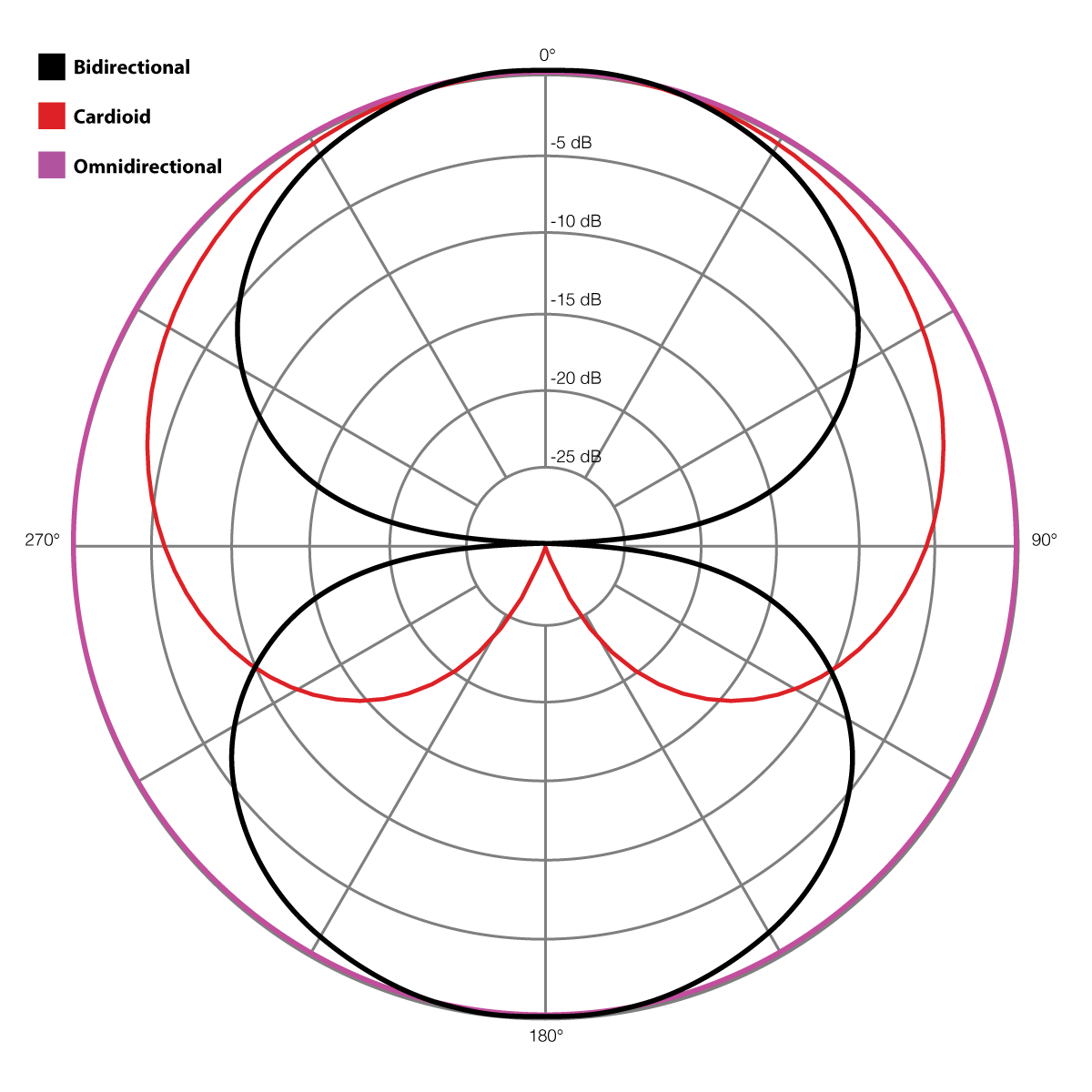

Below are what are known as polar patterns that represent the ways that different mics pickup sound. To understand these images, imagine that you are looking down on a microphone set in the middle circle (just like you were looking down on a globe from the North Pole).

As you will see from the first diagram, omnidirectional mics pickup sound in a 360 degree radius. On the other hand, cardioid mic captures sound best from the front, but also captures sound to its sides.

Polar Patterns for Microphones by Jason M. Kelly, Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Supercardioid and Directional Shotgun Patterns by Galak76 Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. Cardioid Polar Pattern by Nicoguaro Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

Dynamic vs. Condenser (a.k.a. Capacitor) Mics

Dynamic mics and a condenser mics contrast in their capacity to pick up sound quality. The difference between a dynamic mic and a condenser mic is the difference between an SUV and a sports car. The dynamic mic can handle rougher conditions and loud volumes (a.k.a. Sound Pressure Level, or SPL). Condenser mics are better with more subtle sounds and variations and are ideal for capturing the modulations of the human voice and acoustic instruments.

For oral histories in a controlled environment, such as as a studio, condenser mics are generally preferred. They are going to record a higher quality of sound. However, for recording the soundscape of a work site for a history project, the dynamic mic might be a better choice.

Without going into detail about the engineering differences between dynamic and condenser mics, it’s sufficient to know that condenser mics require external power. This can come from an external power box, from a battery in the mic itself, or from the 3-pin microphone cable via a technology known as “P48 phantom power” or just “phantom power.” Phantom power is (usually) a 48 volt direct current supplied through the preamp connected to the microphone (more on preamps in an upcoming post).

A final item to keep in mind when it comes to dynamic and condenser mics is the cost. Condenser mics can be significantly more expensive than dynamic mics, so it’s worthwhile borrowing some equipment and testing it before making any major investments.

USB vs. XLR MicS

One of the first choices you will need to make is whether you want to use a USB or an XLR mic. On the surface, the difference between the two is the connector. A USB mic can plug directly into your computer, while an XLR mic requires at least a preamp (whether that is built into your recorder or whether it is a separate device altogether).

There are lots of strong opinions about this online, and I have no desire to wade into the argument. I have used both. A good USB mic (such as those from the Blue company) can do a great job if you’re doing basic home recordings. However, the moment you want to get a little bit more advanced in your recording technique—and, by more advanced, I mean something as simple as having two USB mics attached to a single computer—you begin to see the limits of the USB setup.

I much prefer an XLR system, which allows for lots of customization. It also allows you to swap in new devices quite easily as you become more advanced. And, if a part breaks, you don’t have to buy a whole new system. With an XLR setup, you will run your mics through a preamp, which might have more or less advanced mixing capabilities, right into your recording device. For basic podcasts, I use two mics that run into a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 preamp, which outputs via USB to my computer running GarageBand. Then, I do all my audio editing in GarageBand.