A Multimedia Story of The “Bonus Army”: In 1932, the U.S. Government Used Tanks and Tear Gas on Its WWI Veterans

After the financial crash of 1929, unemployment rates soared. Millions of Americans couldn't afford food or a place to live. Shanty towns--named Hoovervilles, after President Herbert Hoover--developed across the country.

Berenice Abbot. Hooverville at West Houston and Mercer in Manhattan. 1935. New York Public Library.

In May 1932 in Washington, D.C., a group of WWI veterans and their family members began setting up Hoovervilles (and taking up residence in abandoned buildings) as organizing locations to press the government to release their service bonuses early—to support them in their moment of deepest need. This group and their fellow demonstrators became known as the “Bonus Army.”

The largest camp—Camp Marks—was in Anacostia. With training in building facilities and sanitation, the veterans were well ordered and maintained registers of the individuals in the camp.

Bonus Army Camp, Anacostia, Washinton, DC. 1932. Washington Area Spark. Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The bonuses the veterans were requesting was money that the government promised them in 1924 through the World War Adjusted Compensation Act. The problem with the act, also known as the “Bonus Act,” was that veterans could not receive the money until 1945, except according to certain limited provisions.

Adjusted Service Certificate for Ed Akins. 1925. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adjusted_Service_Certificate.jpg

Veterans from cities across the United States converged in Washington, D.C. in 1932, in part due to the work of Walter W. Waters, a veteran who was living in Portland, Oregon. In the March 1932 National Veterans Association meeting, he argued that veterans should converge on the capital and argue their case. By May, he and a group of 300 others were boarding livestock cars for the trip east. They were helped by railroad workers, many of whom were also veterans. News spread by radio, and contingents of the “Bonus Expeditionary Force” (B.E.F.)—as they called themselves—emerged across the country.

News clipping of leaders of the Bonus Expeditionary Force.

Sewilla LaMar, who lost both her husband and brother in WWI, participated in the Bonus March, recording her experiences in an article for Abbott’s Monthly. Riding boxcars and walking from Los Angeles, she explained why she made the trip:

“I, like millions of mothers, have suffered the ravages of war. Somewhere over there lie the bodies of my husband and my brother, who gave their all in the World War.”

Her advocacy came at a substantial cost. In Iowa, she was attacked by veterans while traveling in the freight cars:

“I did not mind the loss of these valuables so much but the bruises and humiliation I suffered on this mission of mercy will perhaps remain with me for the rest of my life,”

In LaMar’s article, she expressed a deep awareness of the importance of the march, especially for its potential to illuminate the ways in which Jim Crow and class exploitation intersected.

“It was Jim Crow ships that took our boys over there, and under the Hoover administration, it was Jim Crow ships that took the Gold Star mothers to the graves of their sons who were left in Flanders’ Fields. Jim Crow, it seemed, stood out above all else. It was only the denial of the bonus plea which affected both black and white veterans alike.”

Cover of Abbott’s Monthly (September 1932).

Like LaMar, Roy Wilkins, a reporter for NAACP’s The Crisis, recognized the significance of the moment. He reflected on the fact that while U.S. generals had long said that troops needed to remain segregated the veterans had desegregated the camps.

In gadding about I came across white toes and black toes sticking out from tent flaps and boxes as their owners sought to sleep away the day. They were far from the spouters of Nordic nonsense, addressing themselves to the business of living together. They were in another world, although Jim Crow Washington, D.C. was only a stone's throw from their doors.

Wilkins’s conclusion was that the soldiers’ common economic conditions created the conditions for solidarity across racial lines—that they had (for the most part) banned Jim Crow.

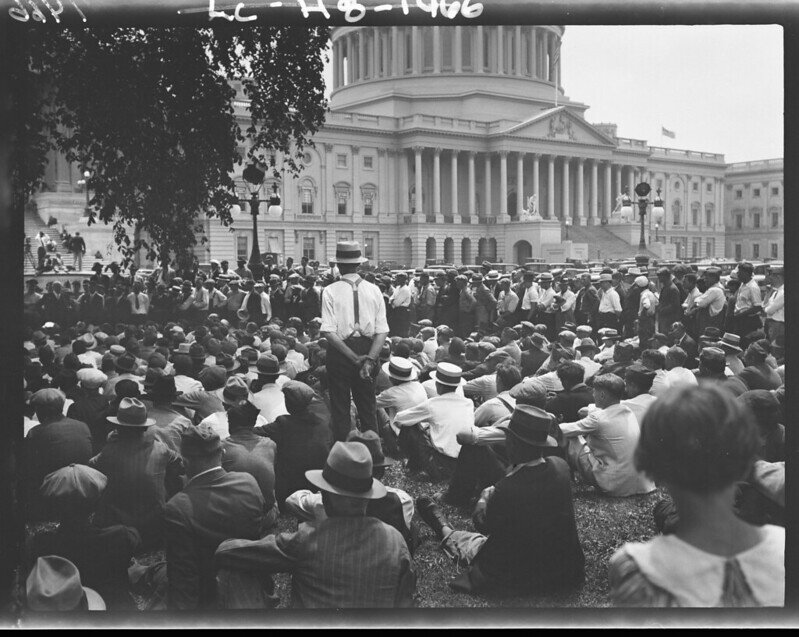

Support for the Bonus Army grew. During the 1932 congress, the House of Representatives responded to veterans’ demands by passing the Wright Patman Bonus Bill (211-176). With this momentum, up to 40,000 members of the Bonus Army marched to the Capitol Building on June 17 to demonstrate for Senate support. They were handed a defeat by Senators (62-18).

Concerned by the threat posed by tens of thousands of unemployed and organized veterans in the capital—and, no doubt, the breakdown of segregated communities—the government was keen to paint the protestors as criminals and communists. Under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI kept a growing file on the Bonus March and associated demonstrations—feeding information to Congress and the President of the threat of communism.

A page from the FBI files claiming that the communists were behind the Bonus Army and that the presence of the Bonus Army increased the activity of communists in Washington, D.C.

The Bonus Army was a well organized, self-regulating organization. And, in the wake of their defeat in congress, they continued to push for reforms. In late June 1932, they began publishing The B.E.F. News.

The first issues encourage the Bonus Army to stay in place and push for their rights, linking their own rights as veterans to those of Americans across the country:

The feeling among the veterans at the camps is that three years have now been wasted in dilatory tactics. They feel that the leaders of the nation have woefully misrepresented the tragedy of the American people, that a deliberate effort to misrepresent and minimize actual suffering has been made, and that there can be no hope for relief unless a resolute course is followed.

The veterans, moreover, are interested not only in relief for veterans and their families. Their view of pressing needs takes in all the American citizens who now suffer from unemployment and penury. Their reaction to the present situation may be summed up in a single elemental thought: Billions for the bankers who wrecked the nation, but nothing for the humble people who face privation and misery.

In the third issue (9 July 1932), the writers compare their peaceful organizing work to that of Ghandi. And, in response to the government’s offer to allow veterans to borrow against the amount each soldier was owed—effectively attempting to split the B.E.F. with a moderate concession—they write:

The watch-word is: 'Stick!' If we retreat now we cravenly surrender the advance thus far made. Moreover, we desert the cause of those millions of destitute men and women who hopefully look to us for leadership.

Even if you accept the miserable loan--your own money--use it for a trip home to see your family. Then come back. And bring recruits.

The fight for hungry Americans must go on.

The organizers were well aware that their opposition was attempting to brand them as communists as a way to undermine their credibility with the American public. In response, the newspaper openly disavowed communism and suggested that it was possible that so-called communists in their ranks could in fact be government secret service agents attempting to encourage the Bonus Army members to take “extreme measures.”

The B.E.F. News. Volume 1, issue 1 (25 June 1932). Washington Area Spark. Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The B.E.F. News. Volume 1, issue 1 (9 July 1932). Washington Area Spark. Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

On 19 July, retired Marine Major General Smedley Butler spoke to veterans at the Anacostia Flats camp, encouraging them to continue pursuing their just cause.

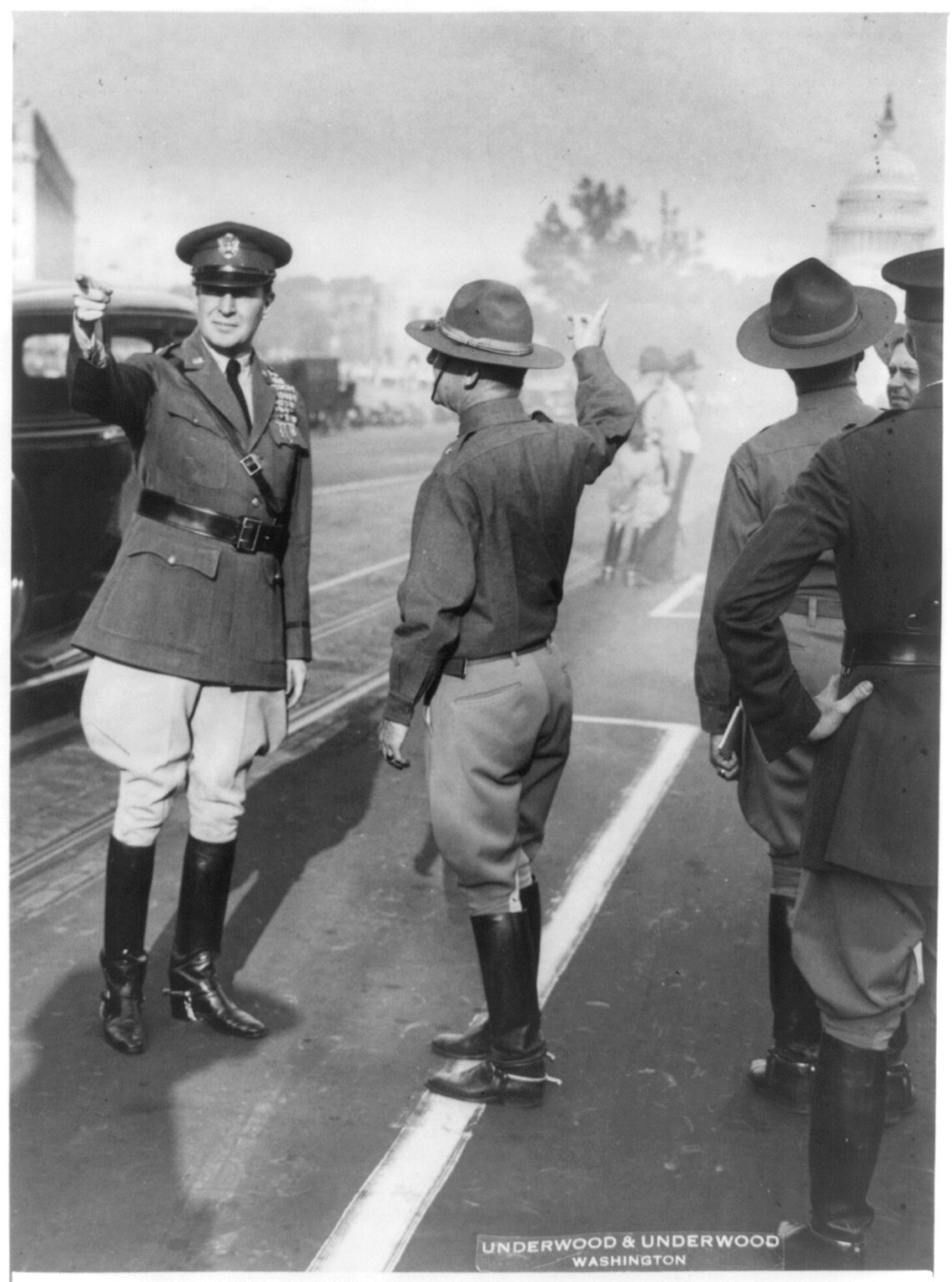

On 28 July 1932, the government used the U.S. military to begin removing protestors from abandoned buildings in the area that has become known as the Federal Triangle. Under orders from the Attorney General to clear all federal property, Washington Police Chief Pelham Glassford led his department in evicting veterans. Some resisted, and when one of them grabbed the nightstick of Officer George A. Shinault, the officer used his gun to kill two of them.

As word made its way to veterans at Camp Marks in Anacostia, thousands of veterans crossed the 11th Street Bridge to confront the police. This gave the U.S. Army, led by Douglas Macarthur and George S. Patton, their opportunity to move in and escalate the conflict. The veterans were likely unaware of the draconian beliefs of these two generals. Patton, for example, took the position that

a few casualties become martyrs, a large number an object lesson…If an enemy is met in a street, deploy completely across the street in close order and direct him to fall back, unless he is in equal or smaller numbers, in which case keep moving and use the bayonet to encourage his retreat. If they are running, a few good wounds in the buttocks will encourage them. If they resist, they must be killed. (Patton, “Federal Troops in Domestic Disturbances,” November 1932).

Onlookers and some veterans first imagined that the troop movements were a military parade and applauded the soldiers. Soon, however, the soldiers turned their bayonets, sabres, horses, and tanks on the crowd. The army gassed the WWI veterans to clear the Hoovervilles.

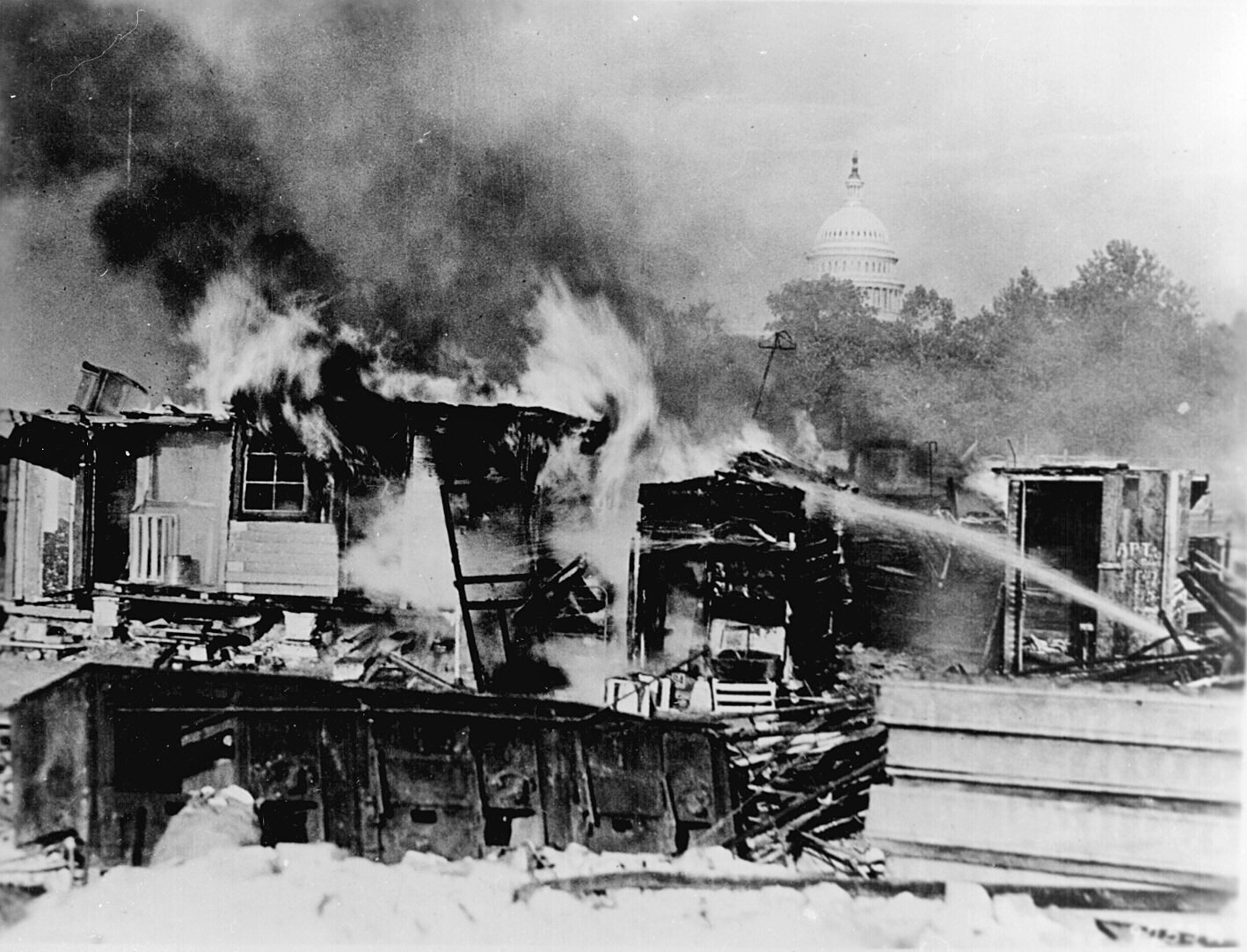

While President Hoover had ordered Macarthur not to cross the Anacostia River, the general ignored the order and attacked Camp Marks, burning it to the ground. The fires burned into the evening, lighting up the D.C. skyline.

Department of Defense. Department of the Army. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. 9/18/1947-2/28/1964. Series: Historical Films, ca. 1914 - ca. 1936. U.S. National Archives.

While the soldiers had lost the battle, they had not lost the war. They retreated to Johnstown, Pennsylvania where they found refuge for a short time.

Bonus Army in Ideal Park near Johnstown, PA, 3 August 1932.

Congress finally conceded to the veterans demands in 1936, passing legislation allowing them to receive their bonuses. Opposed by President Roosevelt, the Senate overrode his veto, giving the veterans the bonuses that they had been promised 12 years earlier.

The cover of the evening edition of the New York Times for 28 January 1936.

As with all social movements, the B.E.F.’s work was accompanied by poetry, music, and art. In the section below, you can listen to a number of songs from the 1930s that make direct reference to the Bonus Army and its demands. The earliest is “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime,” which was first performed and recorded in late 1932. It speaks of an everyman who has been abandoned by his country. You will notice several references to soldiers who request to be recognized by their country. Joe Pullum, Peetie Wheatstraw, Red Nelson, and Bumble Bee Slim recorded blues songs that look forward to the day when their bonuses arrive. And, Lil Johnson sings “That Bonus Done Gone Through” in celebration of Congress finally conceding to the demands of WWI veterans in 1936.

Joan Blondell and Etta Moten. “Remember My Forgotten Man” from Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933).

Have you heard the latest news?

These veterans ain’t got no more blues!

They are planning what to do

Since that bonus done gone through!

Now, where’s that man you used to rave about?

It’s time now to see what he’s made out

You’d better not let him slip through your hands

‘Cause some other woman will surely take your man!

Come on, girls! Yes! Ain’t you going downtown? Yes!

What you gonna buy? A new evening gown!

Oooooh, a new pair of shoes!

Oooooh, gonna truck away those blues!

‘Cause that bonus done gone through!

(spoken:

Beat it out, boy!

Say, Bob!

Yes?

Ain’t you gettin’ your bonus?

Sure, baby!

You’ll go up when the wagon comes

Come up and see me sometime

Sure, baby, when I get my bonus!)

Now when you steps out on the street

All lookin’ so nice and neat

Everybody will stare at you so

Now look here, folks, she’s out the bear once more

Now when I get all togged down

Men’s will come from miles around

Go on, boys, I ain’t got no time to lose

I got a good veteran who has cured my blues

Come on, girls!

Yes!

Ain’t you going downtown?

Yes!

What you gonna buy?

A new evening gown!

Oooooh, listen to my call!

Oooooh, just watch this Mae West walk!

‘Cause that bonus done gone through!

‘Cause that bonus done gone through!